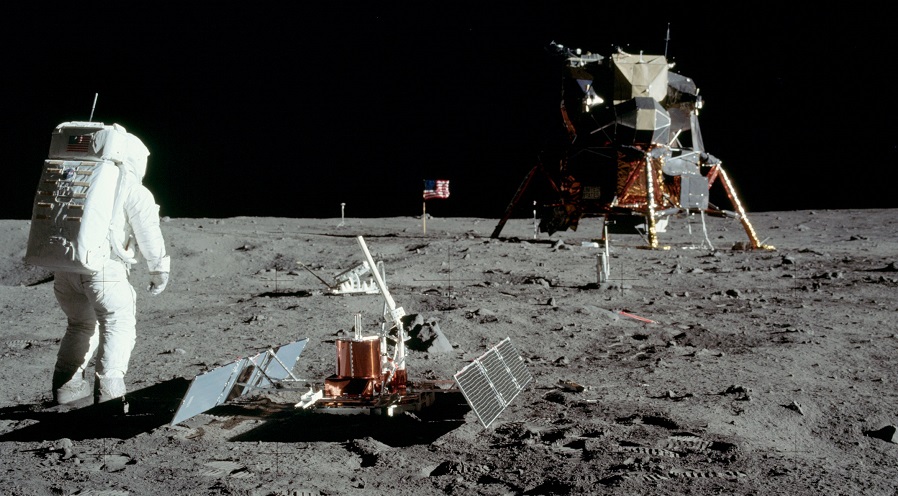

The most effective means of walking seemed to be the lope that evolved naturally.

Continuing First Men on Moon,

our selection from Apollo 11 Mission Report by NASA Mission Evaluation Team and by The Astronauts: Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins published in 1971. The selection is presented in eight easy 5-minute installments. For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in First Men on Moon

Time: July 21, 1969

Place: Sea of Tranquility

Public domain image from Wikipedia

Platform alignment and preparation for early lift-off were completed on schedule without significant problems. The mission timer malfunctioned and displayed an impossible number that could not be correlated with any specific failure time. After several unsuccessful attempts to recycle this timer, it was turned off for 11 hours to cool. The timer was turned on for ascent, and it operated properly and performed satisfactorily for the remainder of the mission. (See “Mission Timer Stopped” in section 16.)

The crew had given considerable thought to the advantage of beginning the extravehicular activity as soon as possible after landing instead of following the flight plan schedule and having the surface operations between two rest periods. The initial rest period was planned to allow flexibility in the event of unexpected difficulty with postlanding activities. These difficulties did not materialize. The crewmen were not overly tired, and no problem was experienced in adjusting to the 1/6-g environment. Based on these facts, the decision was made at 104:40:00 to proceed with the extravehicular activity prior to the first rest period.

Preparation for extravehicular activity began at 106:11:00. The estimate of the preparation time proved to be optimistic. In simulations, 2 hours had been found to be a reasonable allocation; however, everything had also been laid out in an orderly manner in the cockpit, and only those items involved in the extravehicular activity were present. In actual use, checklists, food packets, monoculars, and other items interfered with an orderly preparation. All these items required some thought as to their possible interference or use in the extravehicular activity. This interference resulted in exceeding the time line estimate by a considerable amount. Preparation for egress was conducted slowly, carefully, and deliberately, and future missions should be planned and conducted with the same philosophy. The extravehicular activity preparation checklist was adequate and was followed closely. However, minor items that required a decision in real time or that had not been considered before flight required more time than anticipated.

An electrical connector on the cable that connects the remote control unit to the portable life support system gave some trouble in mating. (See “Mating of Remote Control Unit to Portable Life Support System” in section 16.) This problem had been encountered occasionally with the same equipment before flight. At least 10 minutes were required in order to connect each unit, and at one point it was thought the connection would not be successfully completed.

Considerable difficulty was experienced with voice communications when the extravehicular transceivers were used inside the lunar module. At times, communications between the ground and the lunar module were good, but at other times they were garbled for no obvious reason. Outside the vehicle, no appreciable communications problems occurred. Upon ingress from the surface, communications difficulties recurred, but under different conditions. That is, the voice dropouts to the ground were not repeatable in the same manner.

Depressurization of the lunar module was one aspect of the mission that had never been completely performed on the ground. In the various altitude chamber tests of the spacecraft and the extravehicular mobility unit, a complete set of authentic conditions was never present. The depressurization of the lunar module through the bacteria filter took much longer than had been anticipated. The indicated cabin pressure did not go below 0.1 psi, and some concern was experienced in opening the forward hatch against this residual pressure. The hatch appeared to bend on initial opening, and small particles appeared to be blown out around the hatch when the seal was broken. (See “Slow Cabin Decompression” in section 16.)

Simulation work in both the water immersion facility and the 1/6-g environment in an airplane was reasonably accurate in preparing the crew for lunar module egress. Body positioning and arching-the-back techniques were performed in exiting the hatch, and no unexpected problems were experienced. The forward platform was more than adequate to allow changing the body position from that used in egressing the hatch to that required for getting on the ladder. The first ladder step was somewhat difficult to see and required caution and forethought. In general, the hatch, porch, and ladder operations were not particularly difficult and caused little concern. Operations on the platform could be performed without losing body balance, and adequate maneuvering room was available.

The initial operation of the lunar equipment conveyor in lowering the camera was satisfactory, but after the straps had become covered with lunar surface material, a problem arose in transporting the equipment back into the lunar module. Dust from this equipment fell back onto the lower crewmember and into the cabin and seemed to bind the conveyor so that considerable force was required in order to operate the conveyor. Alternatives in transporting equipment into the lunar module had been suggested before flight, and although no opportunity was available to evaluate these techniques, the alternatives might have been an improvement over the conveyor.

Work in the l/6-g environment was a pleasant experience. Adaptation to movement was not difficult, and movement seemed to be natural. Certain specific peculiarities, such as the effect of the mass as compared to the lack of traction, can be anticipated; but complete familiarization need not be pursued.

The most effective means of walking seemed to be the lope that evolved naturally. The fact that both feet were occasionally off the ground at the same time, plus the fact that the feet did not return to the surface as rapidly as on earth, required some anticipation before an attempt to stop. Noticeable resistance was provided by the suit, although movement was not difficult.

On future flights, crewmembers may want to consider kneeling in order to work with their hands. Getting to and from the kneeling position would be no problem and being able to do more work with the hands would increase productive capability.

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

More information here and here, and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.