Today’s installment concludes First Men on Moon,

our selection from Apollo 11 Mission Report by NASA Mission Evaluation Team and by The Astronauts: Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins published in 1971.

If you have journeyed through all of the installments of this series, just one more to go and you will have completed a selection from the great works of eight thousand words. Congratulations! For works benefiting from the latest research see the “More information” section at the bottom of these pages.

Previously in First Men on Moon

Time: July 22-24, 1969

Place: Space, Between the Moon and the Earth

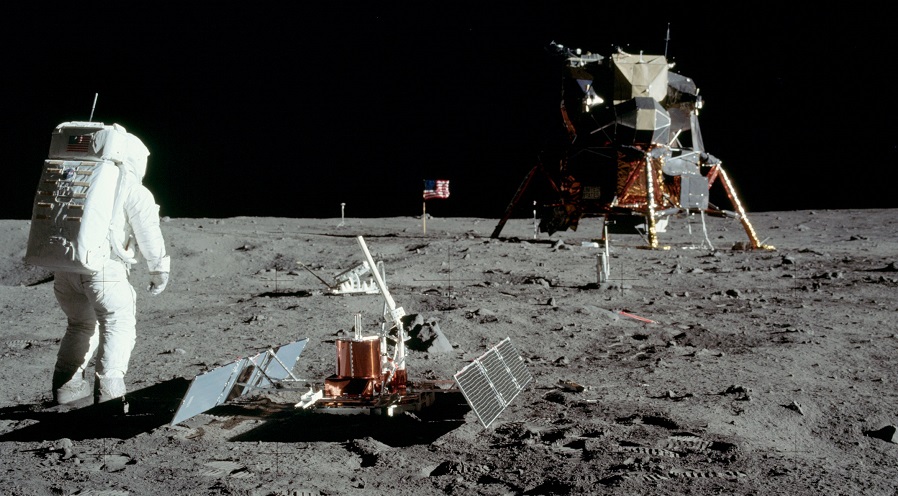

Public domain image from Wikipedia

The small out-of-plane velocities that existed between the spacecraft orbits indicated a highly accurate lunar surface alignment. As a result of the higher-than expected ellipticity of the command module orbit, backup chart solutions were not possible for the first two rendezvous maneuvers, and the constant-differential height maneuver had a higher-than-expected vertical component. The computers in both spacecraft agreed closely on the maneuver values, and the lunar module primary guidance computer solution was executed by using the minus X thrusters.

During the co-elliptic phase, radar tracking data were inserted into the abort guidance system to obtain an independent intercept guidance solution. The primary guidance solution was 6-1/2 minutes later than planned. However, the intercept trajectory was nominal , with only two small midcourse corrections of 1.0 and 1.5 ft/sec. The line-of-sight rates were low, and the planned braking schedule was used to reach a station-keeping position.

In the process of maneuvering the lunar module to the docking attitude, while at the same time avoiding direct sunlight in the forward windows, the platform inadvertently reached gimbal lock. The docking was completed by using the abort guidance system for attitude control.

Predocking activities in the command module were normal in all respects, as was docking up to the point of probe capture. After the Command Module Pilot ascertained that a successful capture had occurred, as indicated by “barberpole” indicators, the CMC-FREE switch position was used and one retract bottle fired. A right yaw excursion of approximately 15° took place immediately for 1 or 2 seconds. The Command Module Pilot went back to the CMC-AUTO switch position and made hand-controller inputs to reduce the angle between the two vehicles to zero. At docking, thruster firings occurred unexpectedly in the lunar module when the retract mechanism was actuated, and attitude excursions of up to 15° were observed. The lunar module was manually realigned. While this maneuver was in progress, all 12 docking latches fired, and docking was completed successfully. (See “Guidance, Navigation, and Control” in section 8.)

Following docking, the tunnel was cleared, and the probe and drogue were stowed in the lunar module. The items to be transferred to the command module were cleaned by using a vacuum brush attached to the lunar module suit return hose. The suction was low, and as a result, the process was rather tedious. The sample return containers and film magazines were placed in appropriate bags to complete the transfer, and the lunar module was configured for jettison according to the checklist procedure.

The time between docking and transearth injection was more than adequate to clean all equipment contaminated with lunar surface material and to return it to the command module for stowage so that the necessary preparations for transearth injection could be made. The transearth injection maneuver, the last service propulsion engine firing of the flight, was nominal. The only difference between the transearth maneuver and previous firings was that without the docked lunar module, the start transient was apparent.

During transearth coast, faint spots or scintillations of light were observed within the command module cabin. These phenomena became apparent after the Commander and the Lunar Module Pilot became dark-adapted and relaxed.

[NASA Editor’s note: The source or cause of the light scintillations is as yet unknown. One explanation involves primary cosmic rays with energies in the range of billions of electron volts bombarding an object in outer space. The theory assumes that numerous heavy and high-energy cosmic particles penetrate the command module structure, causing heavy ionization inside the spacecraft. When liberated electrons recombine with ions, photons in the visible portion of the spectrum are emitted. If a sufficient number of photons is emitted, a dark-adapted observer can detect the photons as a small spot or a streak of light. Two simple laboratory experiments were conducted to substantiate the theory, but no positive results were obtained in a 5-psi pressure environment because a high enough energy source was not available to create the radiation at that pressure. This level of radiation does not present a crew hazard.]

Only one midcourse correction, a reaction control system firing of 4.8 ft/sec, was required during transearth coast. In general, the transearth coast period was characterized by a general relaxation on the part of the crew, with plenty of time available to sample the excellent variety of food packets and to take photographs of the shrinking moon and the growing earth.

Because of the presence of thunderstorms in the primary recovery area (1285 miles down range from the entry interface of 400 000 feet), the targeted landing point was moved to a range of 1500 miles from the entry interface. This change required the use of computer program P65 (skip-up control routine) in the computer, in addition to those programs used for the planned shorter range entry. This change caused the crew some apprehension because such entries had rarely been practiced in preflight simulations. However, during the entry, these parameters remained within acceptable limits. The entry was guided automatically and was nominal in all respects. The first acceleration pulse reached approximately 6.5g, and the second reached 6,0g.

Upon landing, the 18-knot surface wind filled the parachutes and immediately rotated the command module into the apex down (stable II) flotation position prior to parachute release. Moderate wave-induced oscillations accelerated the uprighting sequence, which was completed in less than 8 minutes. No difficulties were encountered in completing the postlanding checklist.

The biological isolation garments were donned inside the spacecraft. Crew transfer into the raft was followed by hatch closure and by decontamination of the spacecraft and crewmembers by means of germicidal scrubdown.

Helicopter pickup was performed as planned, but visibility was substantially degraded because of moisture condensation on the biological isolation garment faceplate. The helicopter transfer to the aircraft carrier was performed as quickly as could be expected, but the temperature increase inside the suit was uncomfortable. Transfer from the helicopter into the mobile quarantine facility completed the voyage of Apollo 11.

| <—Previous | Master List |

This ends our series of passages on First Men on Moon by NASA Mission Evaluation Team and The Astronauts: Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin, and Michael Collins from NASA’s Apollo 11 Mission Report published in 1971. This blog features short and lengthy pieces on all aspects of our shared past. Here are selections from the great historians who may be forgotten (and whose work have fallen into public domain) as well as links to the most up-to-date developments in the field of history and of course, original material from yours truly, Jack Le Moine. – A little bit of everything historical is here.

More information here and here and below.

|

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.