Egyptians tell Herodotus that they base their version of the story of Helen of Troy upon inquiries of Menelaus himself.

Translated by George C. Macaulay — our special project presenting the complete Herodotus with URLs for all of those people, places, events, and things which baffles and discourages modern readers.

Previously on Herodotus

112. After him, they said, there succeeded to the throne a man of Memphis, whose name in the tongue of the Hellenes was Proteus; for whom there is now a sacred enclosure at Memphis, very fair and well ordered, lying on that side of the temple of Hephaistos which faces the North Wind. Round about this enclosure dwell Phoenicians of Tyre, and this whole region is called the Camp of the Tyrians. Within the enclosure of Proteus there is a temple called the temple of the “foreign Aphrodite,” which temple I conjecture to be one of Helen the daughter of Tyndareus, not only because I have heard the tale how Helen dwelt with Proteus, but also especially because it is called by the name of the “foreign Aphrodite,” for the other temples of Aphrodite which there are have none of them the addition of the word “foreign” to the name.

113. And the priests told me, when I inquired, that the things concerning Helen happened thus:–Paris having carried off Helen was sailing away from Sparta to his own land, and when he had come to the Aegean Sea contrary winds drove him from his course to the Sea of Egypt; and after that, since the blasts did not cease to blow, he came to Egypt itself, and in Egypt to that which is now named the Canobic mouth of the Nile and to Taricheiai. Now there was upon the shore, as still there is now, a temple of Hercules, in which if any man’s slave take refuge and have the sacred marks set upon him, giving himself over to the god, it is not lawful to lay hands upon him; and this custom has continued still unchanged from the beginning down to my own time. Accordingly the attendants of Paris, having heard of the custom which existed about the temple, ran away from him, and sitting down as suppliants of the god, accused Paris, because they desired to do him hurt, telling the whole tale how things were about Helen and about the wrong done to Menelaos; and this accusation they made not only to the priests but also to the warden of this river-mouth, whose name was Thonis.

[This is a very different version than the common one. Herodotus believed Helen spent the Trojan War in Egypt, not Troy. – JL]

114. Thonis then having heard their tale sent forthwith a message to Proteus at Memphis, which said as follows: “There hath come a stranger, a Trojan by race, who hath done in Hellas an unholy deed; for he hath deceived the wife of his own host, and is come hither bringing with him this woman herself and very much wealth, having been carried out of his way by winds to thy land. Shall we then allow him to sail out unharmed, or shall we first take away from him that which he brought with him?” In reply to this Proteus sent back a messenger who said thus: “Seize this man, whosoever he may be, who has done impiety to his own host, and bring him away into my presence, that I may know what he will find to say.”

115. Hearing this, Thonis seized Paris and detained his ships, and after that he brought the man himself up to Memphis and with him Helen and the wealth he had, and also in addition to them the suppliants. So when all had been conveyed up thither, Proteus began to ask Paris who he was and from whence he was voyaging; and he both recounted to him his descent and told him the name of his native land, and moreover related of his voyage, from whence he was sailing. After this Proteus asked him whence he had taken Helen; and when Paris went astray in his account and did not speak the truth, those who had become suppliants convicted him of falsehood, relating in full the whole tale of the wrong done.

At length Proteus declared to them this sentence, saying, “Were it not that I count it a matter of great moment not to slay any of those strangers who being driven from their course by winds have come to my land hitherto, I should have taken vengeance on you on behalf of the man of Hellas, seeing that you, most base of men, having received from him hospitality, did work against him a most impious deed. For you did go in to the wife of your own host; and even this was not enough for you, but you did stir her up with desire and have gone away with her like a thief. Moreover not even this by itself was enough for you, but you’ve come here with plunder taken from the house of thy host. Now therefore depart, seeing that I have counted it of great moment not to be a slayer of strangers. This woman indeed and the wealth which you have I will not allow you to carry away, but I shall keep them safe for the Greek who was thy host, until he come himself and desire to carry them off to his home; to yourself however and your fellow-voyagers I proclaim that you depart from your anchoring within three days and go from my land to some other; and if not, that you will be dealt with as enemies.”

116. This the priests said was the manner of Helen’s coming to Proteus; and I suppose that Homer also had heard this story, but since it was not so suitable to the composition of his poem as the other which he followed, he dismissed it finally, making it clear at the same time that he was acquainted with that story also: and according to the manner in which he described the wanderings of Paris in the Iliad (nor did he elsewhere retract that which he had said) it is clear that when he brought Helen he was carried out of his course, wandering to various lands, and that he came among other places to Sidon in Phoenicia. Of this the poet has made mention in the “prowess of Diomede,” and the verses run this: [Illiad VI 289 – JL]

There she had robes many-colored, the works of women of Sidon,

Those whom her son himself the god-like of form Paris

Carried from Sidon, what time the broad sea-path he sailed over

Bringing back Helene home, of a noble father begotten.

And in the Odyssey also he has made mention of it in these verses:

[IV 227 – See Note 1 – JL]

Such had the daughter of Zeus, such drugs of exquisite cunning,

Good, which to her the wife of Thon, Polydamna, had given,

Dwelling in Egypt, the land where the bountiful meadow produces

Drugs more than all lands else, many good being mixed, many evil.

And thus too Menelaos says to Telemachos:

[Oddyssey IV 351 – JL]

Still the gods stayed me in Egypt, to come back hither desiring,

Stayed me from voyaging home, since sacrifice was due I performed not.

In these lines he makes it clear that he knew of the wandering of Paris to Egypt, for Syria borders upon Egypt and the Phoenicians, of whom is Sidon, dwell in Syria.

CC BY-SA 2.0 image from Wikipedia.

There she had robes many-colored, the works of women of Sidon,

Those whom her son himself the god-like of form Paris of Troy

Carried from Sidon, what time the broad sea-path he sailed over

Bringing back Helene home, of a noble father begotten.”

And in the Odyssey also he has made mention of it in these verses:

Such had the daughter of Zeus, such drugs of exquisite cunning,

Good, which to her the wife of Thon, Polydamna, had given,

Dwelling in Egypt, the land where the bountiful meadow produces

Drugs more than all lands else, many good being mixed, many evil.”

And thus too Menelaus says to Telemachos:

Still the gods stayed me in Egypt, to come back hither desiring,

Stayed me from voyaging home, since sacrifice was due I performed not.”

In these lines he makes it clear that he knew of the wandering of Paris of Troy to Egypt, for Syria borders upon Egypt and the Phoenicians, of whom is Sidon, dwell in Syria.

117. By these lines and by this passage it is also most clearly shown that the “Cyprian Epic” was not written by Homer but by some other man: for in this it is said that on the third day after leaving Sparta Paris came to Ilion bringing with him Helen, having had a “gently-blowing wind and a smooth sea,” whereas in the Iliad it says that he wandered from his course when he brought her.

[These references to the Odyssey are by some thought to be interpolations, because they refer only to the visit of Menelaos to Egypt after the fall of Troy; but Herodotus is arguing that Homer, while rejecting the legend of Helen’s stay in Egypt during the war, yet has traces of it left in this later visit to Egypt of Menelaos and Helen, as well as in the visit of Paris and Helen to Sidon.

Herodotus uses geography loosely here. For example, “Syria borders Egypt”.]

118. Let us now leave Homer and the Trojan Epic; but this I will say, namely that I asked the priests whether it is but an idle tale which the Greeks tell of that which they say happened about Troy; and they answered me thus, saying that they had their knowledge by inquiries from Menelaos himself. After the rape of Helen there came indeed, they said, to the Trojan land a large army of Greeks to help Menelaos; and when the army had come out of the ships to land and had pitched its camp there, they sent messengers to Troy, with whom went also Menelaos himself; and when these entered within the wall they demanded back Helen and the wealth which Paris had stolen from Menelaos and had taken away; and moreover they demanded satisfaction for the wrongs done: and the Trojans told the same tale then and afterwards, both with oath and without oath, namely that in deed and in truth they had not Helen nor the wealth for which demand was made, but that both were in Egypt; and that they could not justly be compelled to give satisfaction for that which Proteus the Pharoah of Egypt had. The Greeks however thought that they were being mocked by them and besieged the city, until at last they took it; and when they had taken the wall and did not find Helen, but heard the same tale as before, then they believed the former tale and sent Menelaos himself to Proteus.

119. And Menelaos having come to Egypt and having sailed up to Memphis, told the truth of these matters, and not only found great entertainment, but also received Helen unhurt, and all his own wealth besides. Then however, after he had been thus dealt with, Menelaos showed himself ungrateful to the Egyptians; for when he set forth to sail away, contrary winds detained him, and as this condition of things lasted long, he devised an impious deed; for he took two children of natives and made sacrifice of them. After this, when it was known that he had done so, he became abhorred, and being pursued he escaped and got away in his ships to Libya; but whither he went besides after this, the Egyptians were not able to tell. Of these things they said that they found out part by inquiries, and the rest, namely that which happened in their own land, they related from sure and certain knowledge.

120. Thus the priests of the Egyptians told me; and I myself also agree with the story which was told of Helen, adding this consideration, namely that if Helen had been in Ilion she would have been given up to the Hellenes, whether Alexander consented or no; for Priam assuredly was not so mad, nor yet the others of his house, that they were desirous to run risk of ruin for themselves and their children and their city, in order that Alexander might have Helen as his wife: and even supposing that during the first part of the time they had been so inclined, yet when many others of the Trojans besides were losing their lives as often as they fought with the Hellenes, and of the sons of Priam himself always two or three or even more were slain when a battle took place (if one may trust at all to the Epic poets),–when, I say, things were coming thus to pass, I consider that even if Priam himself had had Helen as his wife, he would have given her back to the Achaians, if at least by so doing he might be freed from the evils which oppressed him. Nor even was the kingdom coming to Alexander next, so that when Priam was old the government was in his hands; but Hector, who was both older and more of a man than he, would have received it after the death of Priam; and him it behoved not to allow his brother to go on with his wrong-doing, considering that great evils were coming to pass on his account both to himself privately and in general to the other Trojans. In truth however they lacked the power to give Helen back; and the Hellenes did not believe them, though they spoke the truth; because, as I declare my opinion, the divine power was purposing to cause them utterly to perish, and so make it evident to men that for great wrongs great also are the chastisements which come from the gods. And thus have I delivered my opinion concerning these matters.

– Herodotus, Book II

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Herodotus made his living by being interesting. In a world where most people did not read and could not afford to buy a book even if they could, they would pay to listen to Herodotus recite from his books. They would not pay to be bored. In that world, the names that populate his stories would have some general familiarity to his audience. Their obscurity to us is a barrier that this series seeks to break down.

MORE INFORMATION

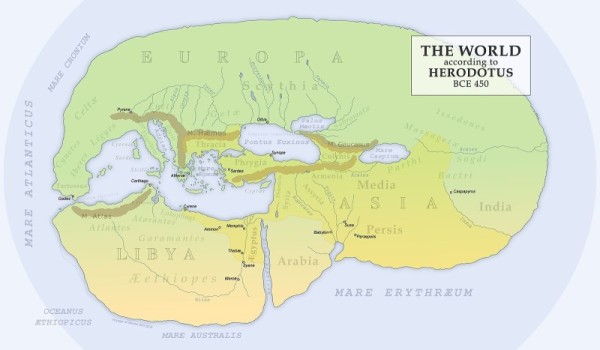

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.