The children switched and the murder covered up.

Translated by George C. Macaulay — our special project presenting the complete Herodotus with URLs for all of those people, places, events, and things which baffles and discourages modern readers.

Previously on Herodotus

111. Having heard this and having taken up the child, the herdsman went back by the way he came, and arrived at his dwelling. And his wife also, as it seems, having been every day on the point of bearing a child, by a providential chance brought her child to birth just at that time, when the herdsman was gone to the city. And both were in anxiety, each for the other, the man having fear about the child-bearing of his wife, and the woman about the cause why Harpagos had sent to summon her husband, not having been wont to do so aforetime. So as soon as he ed and stood before her, the woman seeing him again beyond her hopes was the first to speak, and asked him for what purpose Harpagos had sent for him so urgently. And he said:

Wife, when I came to the city I saw and heard that which I would I had not seen, and which I should wish had never chanced to those whom we serve. For the house of Harpagos was all full of mourning, and I being astonished thereat went within: and as soon as I entered I saw laid out to view an infant child gasping for breath and screaming, which was adorned with gold ornaments and embroidered clothing: and when Harpagos saw me he bade me forthwith to take up the child and carry it away and lay it on that part of the mountains which is most haunted by wild beasts, saying that it was Astyages who laid this task upon me, and using to me many threats, if I should fail to do this. And I took it up and bore it away, supposing that it was the child of some one of the servants of the house, for never could I have supposed whence it really was; but I marveled to see it adorned with gold and raiment, and I marveled also because mourning was made for it openly in the house of Harpagos. And straightway as we went by the road, I learnt the whole of the matter from the servant who went with me out of the city and placed in my hands the babe, namely that it was in truth the son of Mandane the daughter of Astyages, and of Cambyses the son of Cyrus, and that Astyages bade slay it. And now here it is.”

112. And as he said this the herdsman uncovered it and showed it to her. And she, seeing that the child was large and of fair form, wept and clung to the knees of her husband, beseeching him by no means to lay it forth. But he said that he could not do otherwise than so, for watchers would come backwards and forwards sent by Harpagos to see that this was done, and he would perish by a miserable death if he should fail to do this. And as she could not after all persuade her husband, the wife next said as follows:

Since then I am unable to persuade thee not to lay it forth, do thou this which I shall tell thee, if indeed it needs must be seen laid forth. I also have borne a child, but I have borne it dead. Take this and expose it and let us rear the child of the daughter of Astyages as if it were our own. Thus thou wilt not be found out doing a wrong to those whom we serve, nor shall we have taken ill counsel for ourselves; for the dead child will obtain a royal burial and the surviving one will not lose his life.”

113. To the herdsman it seemed that, the case standing thus, his wife spoke well, and forthwith he did so. The child which he was bearing to put to death, this he delivered to his wife, and his own, which was dead, he took and placed in the chest in which he had been bearing the other; and having adorned it with all the adornment of the other child, he bore it to the most desolate part of the mountains and placed it there. And when the third day came after the child had been laid forth, the herdsman went to the city, leaving one of his under-herdsmen to watch there, and when he came to the house of Harpagos he said that he was ready to display the dead body of the child; and Harpagos sent the most trusted of his spearmen, and through them he saw and buried the herdsman’s child. This then had had burial, but him who was afterwards called Cyrus the wife of the herdsman had received, and was bringing him up, giving him no doubt some other name, not Cyrus.

114. And when the boy was ten years old, it happened with regard to him as follows, and this made him known. He was playing in the village in which were stalls for oxen, he was playing there, I say, with other boys of his age in the road. And the boys in their play chose as their king this one who was called the son of the herdsman: and he set some of them to build palaces and others to be spearmen of his guard, and one of them no doubt he appointed to be the eye of the king, and to one he gave the office of bearing the messages, appointing a work for each one severally. Now one of these boys who was playing with the rest, the son of Artembares a man of repute among the Medes, did not do that which Cyrus appointed him to do; therefore Cyrus bade the other boys seize him hand and foot, and when they obeyed his command he dealt with the boy very roughly, scourging him. But he, so soon as he was let go, being made much more angry because he considered that he had been treated with indignity, went down to the city and complained to his father of the treatment which he had met with from Cyrus, calling him not Cyrus, for this was not yet his name, but the son of the herdsman of Astyages. And Artembares in the anger of the moment went at once to Astyages, taking the boy with him, and he declared that he had suffered things that were unfitting and said: “O king, by thy slave, the son of a herdsman, we have been thus outraged,” showing him the shoulders of his son.

CC BY-SA 2.0 image from Wikipedia.

115. And Astyages having heard and seen this, wishing to punish the boy to avenge the honour of Artembares, sent for both the herdsman and his son. And when both were present, Astyages looked at Cyrus and said: “Didst thou dare, being the son of so mean a father as this, to treat with such unseemly insult the son of this man who is first in my favor?” And he replied thus:

Master, I did so to him with right. For the boys of the village, of whom he also was one, in their play set me up as king over them, for I appeared to them most fitted for this place. Now the other boys did what I commanded them, but this one disobeyed and paid no regard, until at last he received the punishment due. If therefore for this I am worthy to suffer any evil, here I stand before thee.”

116. While the boy thus spoke, there came upon Astyages a sense of recognition of him and the lineaments of his face seemed to him to resemble his own, and his answer appeared to be somewhat over free for his station, while the time of the laying forth seemed to agree with the age of the boy. Being struck with amazement by these things, for a time he was speechless; and having at length with difficulty recovered himself, he said, desiring to dismiss Artembares, in order that he might get the herdsman by himself alone and examine him: “Artembares, I will so order these things that thou and thy son shall have no cause to find fault”; and so he dismissed Artembares, and the servants upon the command of Astyages led Cyrus within. And when the herdsman was left alone with the king, Astyages being alone with him asked whence he had received the boy, and who it was who had delivered the boy to him. And the herdsman said that he was his own son, and that the mother was living with him still as his wife. But Astyages said that he was not well advised in desiring to be brought to extreme necessity, and as he said this he made a sign to the spearmen of his guard to seize him. So he, as he was being led away to the torture, then declared the story as it really was; and beginning from the beginning he went through the whole, telling the truth about it, and finally ended with entreaties, asking that he would grant him pardon.

117. So when the herdsman had made known the truth, Astyages now cared less about him, but with Harpagos he was very greatly displeased and bade his spearmen summon him. And when Harpagos came, Astyages asked him thus: “By what death, Harpagos, didst thou destroy the child whom I delivered to thee, born of my daughter?” and Harpagos, seeing that the herdsman was in the king’s palace, turned not to any false way of speech, lest he should be convicted and found out, but said as follows:

O king, so soon as I received the child, I took counsel and considered how I should do according to thy mind, and how without offence to thy command I might not be guilty of murder against thy daughter and against thyself. I did therefore thus: I called this herdsman and delivered the child to him, saying first that thou wert he who bade him slay it — and in this at least I did not lie, for thou didst so command. I delivered it, I say, to this man commanding him to place it upon a desolate mountain, and to stay by it and watch it until it should die, threatening him with all kinds of punishment if he should fail to accomplish this. And when he had done that which was ordered and the child was dead, I sent the most trusted of my eunuchs and through them I saw and buried the child. Thus, O king, it happened about this matter, and the child had this death which I say.”

118. So Harpagos declared the truth, and Astyages concealed the anger which he kept against him for that which had come to pass, and first he related the matter over again to Harpagos according as he had been told it by the herdsman, and afterwards, when it had been thus repeated by him, he ended by saying that the child was alive and that that which had come to pass was well, “for,” continued he,

I was greatly troubled by that which had been done to this child, and I thought it no light thing that I had been made at variance with my daughter. Therefore consider that this is a happy change of fortune, and first send thy son to be with the boy who is newly come, and then, seeing that I intend to make a sacrifice of thanksgiving for the preservation of the boy to those gods to whom that honor belongs, be here thyself to dine with me.”

119. When Harpagos heard this, he did reverence and thought it a great matter that his offence had turned out for his profit and moreover that he had been invited to dinner with happy augury; and so he went to his house. And having entered it straightway, he sent forth his son, for he had one only son of about thirteen years old, bidding him go to the palace of Astyages and do whatsoever the king should command; and he himself being overjoyed told his wife that which had befallen him. But Astyages, when the son of Harpagos arrived, cut his throat and divided him limb from limb, and having roasted some pieces of the flesh and boiled others he caused them to be dressed for eating and kept them ready. And when the time arrived for dinner and the other guests were present and also Harpagos, then before the other guests and before Astyages himself were placed tables covered with flesh of sheep; but before Harpagos was placed the flesh of his own son, all but the head and the hands and the feet, and these were laid aside covered up in a basket. Then when it seemed that Harpagos was satisfied with food, Astyages asked him whether he had been pleased with the banquet; and when Harpagos said that he had been very greatly pleased, they who had been commanded to do this brought to him the head of his son covered up, together with the hands and the feet; and standing near they bade Harpagos uncover and take of them that which he desired. So when Harpagos obeyed and uncovered, he saw the remains of his son; and seeing them he was not overcome with amazement but contained himself: and Astyages asked him whether he perceived of what animal he had been eating the flesh: and he said that he perceived, and that whatsoever the king might do was well pleasing to him. Thus having made answer and taking up the parts of the flesh which still remained he went to his house; and after that, I suppose, he would gather all the parts together and bury them.

– Herodotus, Book I

| <—Previous | Master List | Next—> |

Herodotus made his living by being interesting. In a world where most people did not read and could not afford to buy a book even if they could, they would pay to listen to Herodotus recite from his books. They would not pay to be bored. In that world, the names that populate his stories would have some general familiarity to his audience. Their obscurity to us is a barrier that this series seeks to break down.

MORE INFORMATION

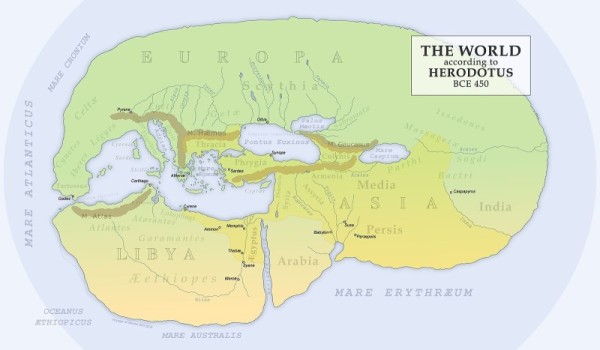

MAP LIBRARY

Because of lack of detail in maps as embedded images, we are providing links instead, enabling readers to view them full screen.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.